Jews in Anykščiai surprised locals with the town’s first gas station and its only bus

Anyone who has visited Anykščiai can easily list at least five, or even all ten, of its most popular sights. The town truly offers plenty to do: culture, entertainment, nature, and wellness services, all supported by an infrastructure comparable to Lithuania’s well-known resorts. And of course, I’d like to share what you can discover here if you’re interested in Jewish heritage.

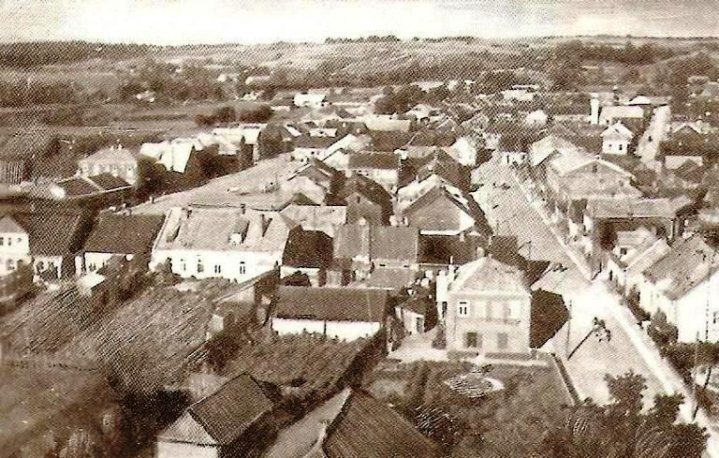

Jews settled in Anykščiai as early as the 17th century. Over time, the community gradually grew. In the 19th century, industrial development and the arrival of the railway led to a significant increase in the Jewish population, reaching its peak at the end of the century. According to the 1897 census, 2,754 Jews lived in Anykščiai, making up nearly 70% of the town’s residents.

A series of devastating fires repeatedly destroyed large parts of the town, often leaving 200 – 400 families homeless. Still, these disasters did not diminish the community as much as the First World War and the pogroms that occurred during it. Jewish residents began returning around 1920, and during the interwar period the community grew again, reaching about 1,800 people.

(photo courtesy: Dr. Michael Libenson, https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/anyksciai/gallery_2.htm)

In Anykščiai – known in Yiddish as Aniksht – the Jewish community lived around the main market square and made their living through crafts and trade. As in many other shtetls, there were blacksmiths, bakers, tailors, shoemakers, butchers, and jewelers. But the Jews of Anykščiai were also involved in the flax trade and in producing felted wool goods.

By 1931, out of 50 Jewish-owned businesses, 14 dealt specifically in grain and flax. And in 1937, among 164 craftsmen in town, 21 were felt-makers – a notable specialty of the local Jews.

People who grew up in Anykščiai remembered the Jews as peaceful, modest, thrifty, and very hardworking. They purchased even items others considered worthless – such as bones or feathers – and still managed to make a profit from them, saving every coin they earned. Jews did not shy away from physically demanding work either: they would float timber rafts down the river Šventoji as far as Jonava and then further on to Germany.

The community also had its own pharmacists and physicians. The best-known were N. Ginsburg, H. Schumacher, and L. Solomin. Lithuanian doctors and pharmacists practiced alongside them, one of them was the famous writer Antanas Vienuolis. Over time, a habit formed: Lithuanian doctors tended to send patients to Lithuanian pharmacies, and Jewish doctors referred theirs to Jewish-run pharmacies.

(Photo: Antanas Baranauskas and Antanas Vienuolis-Žukauskas Memorial Museum)

In the interwar period, the Jews of Anykščiai had three primary schools where instruction was in Hebrew and Yiddish, two large libraries, and a drama club. They were politically active both during the era of Tsarist Russia and in independent Lithuania. In 1920, the Jewish People’s Bank was established.

The Jews of Anykščiai embraced innovation and often initiated new businesses – for example, they opened the town’s first fuel station in the center and operated a bus line to Kaunas. A Jewish townsman, Motke Felcher, discovered and began exploiting the local quartz sand quarries, significantly contributing to the town’s economic development.

(Photo: Antanas Baranauskas and Antanas Vienuolis-Žukauskas Memorial Museum)

From the market square, the narrow Sinagogų, Pirties, and Palestinos streets led to the synagogue square – the shulhoif – where there were perhaps three, perhaps five prayer houses, including a Hasidic synagogue. People recall as many as seven synagogues in Anykščiai. The Jewish cemetery, which has survived to this day, was located on the outskirts of the town at that time – on a hill in the pine grove along today’s Kęstučio Street.

For those who want to try sensing the spirit of the former Jewish shtetl on their own, I suggest a walk of about three hours. Begin your walk in the town’s main square – the former market square.

Old photographs show what the market square once looked like. It was paved with large stones that proved useful on rainy days: traders could hop from stone to stone without getting their feet wet. As Dr. Aron Leiba Skudowitz wrote in his memoirs, a water pump stood in the center of the square. Anyone – rich or poor, Jewish or Christian – could fill their bucket there, and no one ever made an issue of it. “I always wondered,” wrote Dr. Skudowitz, “how such a small pump could hold so much water.”

On Wednesdays, market days, the square was crowded not only with people and horses but also with goats. Poor women would let the goats roam freely, hoping they would eat the hay dropped by the horses. Before the Jewish holidays, the market filled with geese, ducks, and turkeys, and Jewish women’s stalls overflowed with baked goods. Taverns and inns earned well on those days from selling beer and vodka. After the market, the square was left covered with trash and horse manure, which the farmers collected the following morning.

The square, which was smaller in the past, was surrounded almost entirely by Jewish homes, shops, and workshops. Here stood Benderis Itsik’s beer warehouse, Berelis Kagan’s textile shop, the ironmongeries of Tsarne Ratner, Gimpel Lafer, and Faivel Shochot, and nearby lived the photographer Itsik Melnik.

On the eastern side of the square stood a row of brick and wooden buildings. Here you would find both Lithuanian and Jewish shops, a hotel, a pharmacy, and the town’s well-known Jewish-owned fuel pump. At first, it was nothing more than a barrel from which the owner poured fuel using a special container. Later, a hand-operated pump was installed: you had to pump the fuel into a canister first and only then pour it into the car’s tank.

(Photo: Antanas Baranauskas and Antanas Vienuolis-Žukauskas Memorial Museum)

The most beautiful building in Anykščiai, the Pavilionis Hotel (approximately on the site of today’s Anykščiai Cultural Center), housed the well-known pharmacy of Antanas Žukauskas. Just a little to the left, in the building with the small steps, the Zilberman sisters sold haberdashery items. Nearby, children could enjoy sweet Jewish pastries at Lurie’s bakery.

(Photo: A. Baranauskas and A. Vienuolis-Žukauskas Memorial Museum)

Today, the Anykščiai market operates a bit further away, while the main Antanas Baranauskas Square hosts city events, fairs, and festivals.

The blue two-storey wooden house with a gabled roof that still survives today was once the home of Hirsch and Golda Feldmans. Their hotel and restaurant operated there.

Artistic decoration by Romualdas Inčirauskas

Feldman was the first person in town to acquire a bus. The bus would stand right here, in front of the hotel, and once a week it carried townspeople to Kaunas. For children, even sitting in it was an adventure – they would happily wash the bus in exchange for the chance to climb aboard.

At the corner of the square, at the intersection with Šaltupio Street, stands a double red-brick building. Everyone in Anykščiai will tell you that this used to be the lumber shop of the Jewish brothers Shepsel and Meer Rapoport.

Next to the building is the sculptural installation The Bench greeting us as the Sabbath begins. The six identical busts symbolize the six working days of the week, while the bearded figure in a hat represents the festive Shabbat. The sculptor, Romualdas Inčirauskas, who was born in Anykščiai, recalls that in his childhood there was a similar bench here, where elderly women would sit and gossip about passers-by.

Another artwork decorates the wall of the Rapoportas house – a neo-fresco by the artist Lina Šlepavičiūtė depicting the two Grosaite sisters. The poet Miriam Gross-Libenson (1914–2004) emigrated to British-ruled Palestine during the interwar years, while her younger sister Sulamita (along with their parents and other relatives) was murdered in the Holocaust.

In 1938 Miriam returned to Lithuania briefly with her little son. Sulamita begged her sister to take her along to Palestine, but Miriam refused – life there seemed too difficult for a young woman. Miriam regretted that decision for the rest of her life. She continued writing poetry about her hometown for as long as she lived.

As you continue along Šaltupio Street, you will notice several colorful wooden houses – the former Jewish houses – and on the fence of a strict, rectangular brick building hangs an art installation dedicated to the synagogues of Anykščiai. This building is one of the former Jewish prayer houses.

(sculpture by Romualdas Inčirauskas)

A little farther on, behind the Soviet-era apartment blocks, hides a square building with a tall chimney. We are heading toward it. This is one of the surviving synagogues of Anykščiai, and we are now standing in what used to be the Synagogue Square.

By the late 18th century, Anykščiai already had at least two synagogues, a Jewish hospice, and several other community buildings along what was then called New Jewish Street. The synagogues, like the rest of the town’s buildings, were repeatedly destroyed by fires and rebuilt again and again – and with every reconstruction, it seems, there may have been more of them. In the interwar period, there were five or six: the Great (or Old) Synagogue, the New Synagogue, the Shoemakers’ Synagogue, the Hasidic Synagogue, the Talmud Torah, and another prayer house known as the Small Street kloyz. The exact number is difficult to determine today, as sources differ, but let us focus on what remains.

What has survived is the synagogue on Šaltupio Street mentioned earlier, and here, in this square, the square building with the tall chimney. This is the Shoemakers’ Kloyz, built in 1922. The original plans, of course, did not include the chimney: there were arched windows and doors – the traces of which can still be seen if you look closely – a men’s prayer hall on the first floor, a women’s gallery above, and two separate entrances.

The chimney appeared after the war, when the building was turned into a bakery. The windows were bricked up, new ones cut, and the second floor was removed entirely. The building now belongs, it seems, to a private owner – a descendant of Anykščiai’s Jewish community. A few years ago it looked quite abandoned, with boarded-up windows and overgrown bushes, waiting for better days. Recently it has seen some repairs: one corner has been renovated, the doors replaced, and a miniature portrait of the Wandering Jew by Romualdas Inčirauskas has been beautifully incorporated into the façade.

On the site of the Great Synagogue, whose ruins can be seen in old photographs on your right, stands today the Anykščiai Prosecutor’s Office

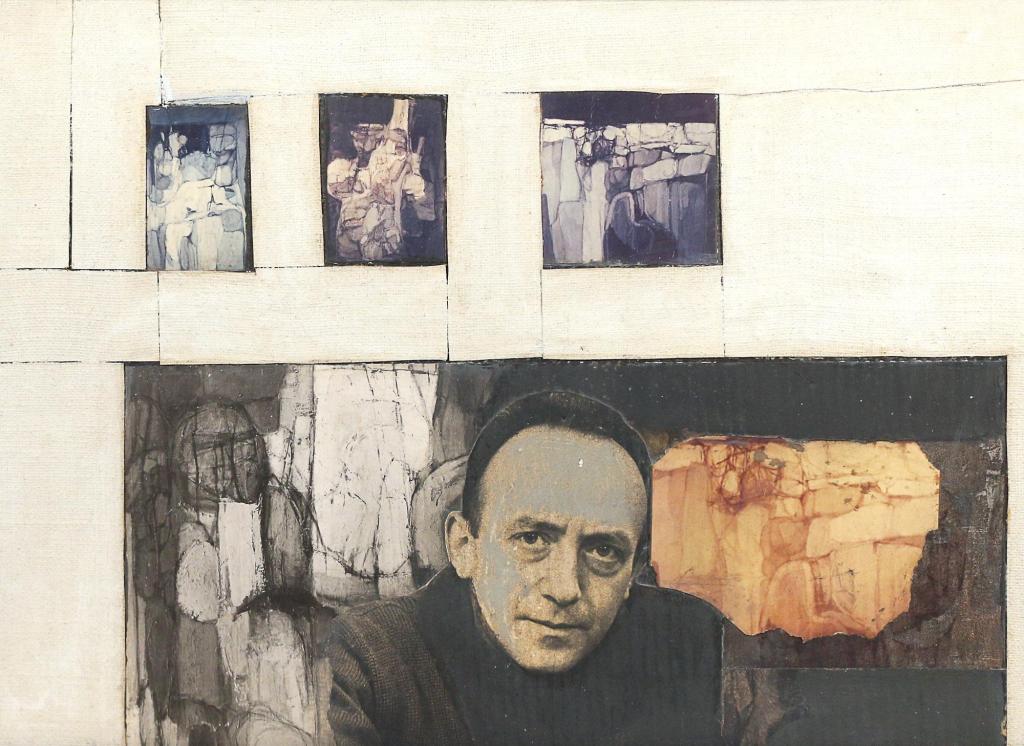

Opposite it stands a sculpture dedicated to perhaps the most famous Jewish native of Anykščiai – Rudolf Baranik (1920–1998). Born in Anykščiai and known then as Ruvim Baranik, he lived here until the age of eighteen, when he left for the United States and went on to gain international recognition for his paintings. Yet memories of his childhood home, town, landscape, and country stayed with him throughout his life. Baranik spoke excellent Lithuanian, wrote for the Lithuanian press in the U.S., and even visited his hometown during the Soviet period.

After Lithuania regained independence, he returned with an exhibition of his works and told the Anykščiai writer Rimantas P. Vanagas that the dominant black-and-white palette in his paintings came from his childhood memories: white snow on the dark rooftops of the town. His works are held in several museums in the U.S. and Sweden; his best-known cycle is The Napalm Elegies, a series of thirty paintings reflecting on the horrors of the Vietnam War.

From here, two narrow, stone-paved lanes lead back toward the central square, still lined with traditional wooden houses. Let’s take a stroll through them.

Sinagogų Street

One of the most picturesque streets in Anykščiai is Simono Daukanto (formerly Palestinos) Street.

A little further ahead, in front of the yellow building, notice the 13 small brass houses created by Romualdas Inčirauskas. They are mounted on the wall next to the fountain and represent the homes of Jewish families who once lived on Palestinos and Sinagogų streets, along with the town’s synagogue.

Those walking more attentively along the same street will notice a plaque embedded in the sidewalk called The Footprint (sculptor Romualdas Inčirauskas). It features the former name of the street, the face of the Wandering Jew, and a poem by Miriam Grosaitė-Libenson – written, appropriately, from right to left.

Stepping back into Antanas Baranauskas Square, I invite you to take a look at a few nearby sights: the former Jewish People’s Bank, the art installation at the Angel Museum featuring interwar Anykščiai telephone-subscribers’ names (created by sculptor Romualdas Inčirauskas), and, of course, to climb the tower of St. Matthew the Apostle Evangelist Church.

Did you spot the former synagogue with the tall chimney? If yes, let’s continue our walk.

The old Jewish cemetery lies on Kęstučio Street, about 600 meters from the town center. A set of stylized gates adorned with the face of the Wandering Jew symbol marks the entrance, together with a memorial stone. On the pine-covered hill you can still see several hundred fragments of gravestones, and from the slope there is a beautiful view of the Anykščiai panorama, with the towers of St. Matthew’s Basilica rising above the town.

Two more sites remain. As always, they bring us to the saddest and most painful chapter in the history of the town’s Jewish community. The destruction of the Jews of Anykščiai began extremely early – already in June 1941 – and was carried out with great brutality. Some people were shot and buried right in the former synagogue square (their remains were later reinterred), others were killed in the cemetery, and most were taken to the forest near the road to Skiemonys, where they were murdered in several stages.

In the summer of 1941, an open-air ghetto was established in what locals call Popo šilelis. Today the site is marked by a small memorial.

The mass murder site lies very close to the Laimės žiburys monument. Following the signs into Liudiškiai Forest, you’ll find a memorial marking the place where around 1,500 Jewish residents of Anykščiai (men, women and children) were killed in the summer of 1941.

I wrote this text based on my own article published in 2020 on the portal We Love Lithuania (in Lithuanian): Žydai Anykščius stebino pirmąja degaline ir vieninteliu autobusu.

Sources:

- Vanagas, R. Žydiškas talismanas. In: Anykščiai XX amžiuje. Vilnius: Petro Ofsetas, 2000, pp. 191–224.

- “Anyksciai” – Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Lithuania

- “Anykščiai”: https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/anyksciai/index.htm

- Vanagas, R. Žiemos nakties dangaus elegijos. Vilnius: Petro Ofsetas, 2020.

- Vanagas, R. Iš vieno grumsto. Anykščiai: Anykščių menų centras, 2023.

- Jakulytė-Vasil, M. Holokausto Lietuvoje atlasas. Vilnius: Valstybinis Vilniaus Gaono žydų muziejus, 2011, p. 238.

- Archival photographs from the collections of the A. Baranauskas and A. Vienuolis-Žukauskas Memorial Museum, published on the Facebook pages Lietuva senose fotografijose and Visit Anykščiai.

- Gross family archival photograph.