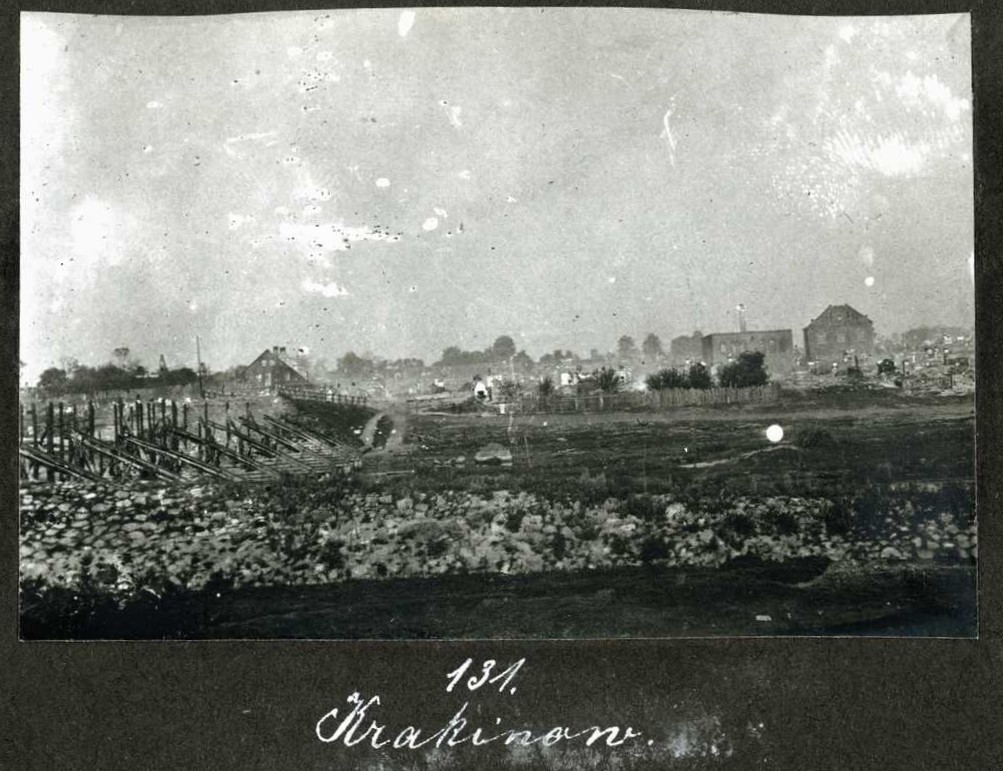

Krekenava is a small town in central Lithuania, set on the right bank of the Nevėžis River. It was first mentioned in 1409. The settlement began to develop more rapidly at the end of the 15th century, when its lands were granted to the Samogitian bishopric. By the mid-16th century Krekenava was already called a miestelis (small town), with a parish church and a manor.

In 1580 the town was granted a privilege of running anual fairs. Over the centuries, the town developed artisan and industrial activities: it was known for brick production, a copper foundry, wood & bark processing, and other trades. The settlement also expanded thanks to river trade and timber rafting along the Nevėžis and Nemunas rivers to the cities of Prussia.

Jews are believed to have settled in Krekenava at the end of the 17th century. In 1727 records mention 18 Jewish families, and by 1775 there were already 55. The town suffered heavily at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries — from devastating fires and the retreating Napoleonic army, which slowed both local and Jewish community growth. Recovery began only in the second half of the 19th century, and Jews played a major part in it: according to the 1897 census, out of 2,187 residents, about 1,500 were Jews.

The outbreak of World War I caused major disruption. The Tsarist authorities, fearing collaboration with the Germans, deported the Jewish residents to the Russian interior. The whole town was burned down.

After the war, only a third returned. Many also emigrated to larger cities, Palestine, the United States, and South Africa. By 1923, the town’s population had dropped to just over 1,000, half of whom were Jewish.

They owned twelve shops, numerous workshops, and small businesses. Many worked as tailors, shoemakers, butchers, barbers, blacksmiths, knitters, painters and glaziers. They traded in grain, flax, leather, shoes, textiles, furs, and medicines, and ran grocery, beverage, and hardware stores. Jews owned two flourmills and a tar factory. By the 1930s, radios and sewing machines were also sold in Krekenava.

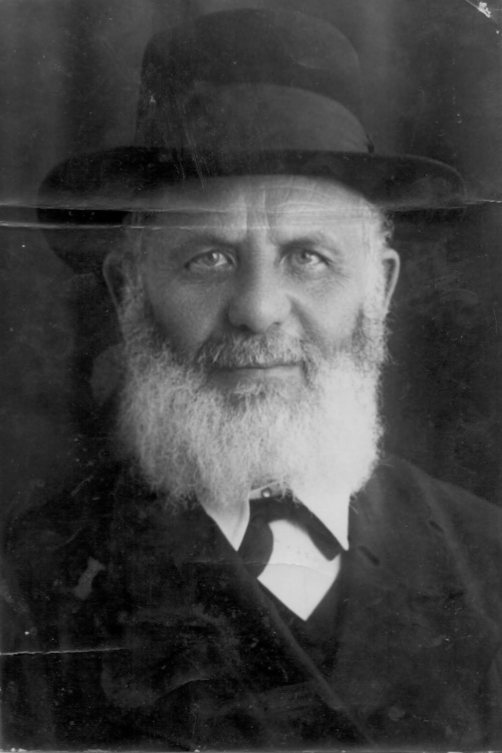

There were a few prayer houses in Krekenava. The Jews called them Shul), Beis Midrash and Kloyz. There was also a small yeshivah with 30 students. Rabbi Moshe Chaskin (1872-1940) served as a Rabbi of Krekenava for 15 years. He emmigrated to Israel in 1933 and became one of the prominent Rabbis of Jerusalem.

Photo: Lietuva senose fotografijose

In the interwar years, Krekenava had a Hebrew Tarbut school with around 170 students, as well as cultural and youth movements such as Maccabi, HeHalutz, and Hashomer Hatzair.

Life in Krekenava is authentically described in Joseph Milne’s article The Krakenowo I remember. As Milne writes:

Now I would like to describe how the houses were constructed in Krakenowo: they were built of timber logs, with moss laid between the logs for protection against heat and cold, and then over laid with smooth planks of wood to give a straight effect. The roofs were made of shingles. The houses had double windows, in order to give protection against the extreme cold, and the inner windows would be removed during the summer. Each window had a shutter with a bar to bolt it from the inside.

Photo: Lietuva senose fotografijose

Photo: Lietuva senose fotografijose

Only Jews lived in the centre of the village, while the non-Jews lived on the outskirts. The non-Jews had gardens in front of their homes, but they lived in little farm-type houses, none of which could compare with the Jewish homes. Some of the poorer Jews, who could not afford to live in the centre of the village in the main streets, had very small houses with thatched roofs, in small side-streets. Because the roofs were made of shingles and of thatch there was always a danger of fire.

Our Beth Hamedrash and our Shul were the largest and most beautiful buildings in the village, and we also had a smaller Shul called the Klauz.

(…) In the Beth Hamedrash, there was a “Lezankah”, a long oven, very low, at the back of the Bimah, to warm up the Synagogue, and many men would gather round on winter evenings to discuss local or world politics. Legends would be told

around the Lezankah, or village new repeated this Chevra Lezankah was their radio and their television!

Presently only one synagogue building, the red one, is surviving, and the gym is established there. The other building, the yellow one, once also was used for the prayer and other Jewish institutions, but after WW2 it was converted into the apartment building.

The Rabbi was held in the highest esteem, and was beloved by all. He was the High Priest, and the Judge. Whenever a dispute arose, whether domestic or family affairs, or in commerce, people never resorted to litigation, but asked the Rabbi to arbitrate. If the elders of the village became aware of a dispute, the Rabbi was notified, and the parties

concerned were called before him for a Din Torah, his judgement being final.

In our village, there was a Schochet to slaughter our cattle and poultry in the ritual manner, but apart from these duties, he assisted in the teaching of the poorer children at the Talmud Torah. We had a Talmud Torah for the teaching of children whose parents could not afford to pay for their tuition. For this purpose the village had a special Schoolhouse, and employed teachers who taught the children Ivri, Chumash and Tanach. Most of the children who attended the Talmud Torah eventually learned one trade or another.

The old Jewish cemetery of Krekenava lies on the opposite bank of the Nevėžis River. Around thirty gravestones have survived, the oldest dating back to 1863 and the most recent to 1937. The local historian and honorary citizen of Panevėžys District, Jonas Žilevičius, once helped restore and fence the cemetery together with others. They also erected a monument marking the site as the former Jewish burial ground.

In 1940, Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union, and in Krekenava, many factories, flourmills, and shops, previously owned by Jews, were nationalized. Zionist parties and youth groups were disbanded, and Hebrew was replaced by Yiddish in the local Jewish school. After the German invasion in June 1941, some Jews tried to flee east but were forced to return. During the German occupation, young Jewish men were arrested and killed, and the remaining community (men, women, and children) was confined to a temporary ghetto under harsh conditions. By late July 1941, most of Krekenava’s Jewish population was transported to Pajuoste airfield and soon after murdered, ending centuries of Jewish life in the town.

A few pictures from Krekenava:

Sources: